There are various ways by which one can hear that an

author that you like has died. Sometimes, you read a short article about his or

her passing in the paper on the way to work. Sometimes there will be something

on the Today programme. In one case I

have received notification of a favourite writer’s death by email because I

subscribe to a website devoted to his works.

In the case of Paul Sussman, however, notification was

received by way of picking up a copy of his fourth and (as it turns out) last novel,

The Labyrinth of Osiris, in a charity

shop and noting from the author blurb that he died last year. He was 46.

I only came across Paul Sussman by chance a few years ago

after working my way through a thriller by another writer that, although OK in

itself, appeared to have been written with a view to cashing in on the success

of The Da Vinci Code (it concerned a

secret about the early history of Christianity which was being concealed by the

Vatican, who were in cahoots with the Mafia). At the end

of the book was an advert – on the lines of ‘if you liked this, you might enjoy

this’ – for another author who shared the same publisher. Intrigued, I looked

for it in my local library and thus did I find The Last Secret of the Temple by Paul Sussman.

It was a superb read – a refreshingly intelligent,

complex and fast-paced thriller that combined a murder investigation,

archaeology, the Nazis and the present-day conflict in the Middle East. There

was not one protagonist but two, both of them more believable than Professor

Langdon. Both were cops, one Egyptian (Yusuf Khalifa of the Luxor police) and

the other Israeli (Jerusalem-based Arieh Ben-Roi), and they ended up being

forced to work together to uncover a secret that could hold the key to peace in

the Middle East. The novel looked even-handedly at serious issues such as

racial hatred, religious fanaticism, morality and power, and did so without

resorting to bias, sentimentality or treating the reader like an idiot.

Sadly, I didn’t follow this up with any more Paul Sussman’s books as they did not appear to be on the library list and his wasn’t a name that was readily available on the shelves of Waterstone’s or W.H. Smith’s. But when I saw that copy of The Labyrith of Osiris, I knew that I had to buy it.

I finished reading it today, and do you know what? It’s

brilliant.

The story begins eighty years ago when a man disappears

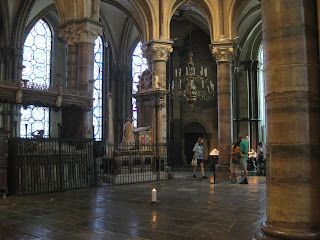

near Luxor, his body being found in the early 1970s. It then jumps to a murder of

an investigative journalist in present-day Jerusalem – in the Armenian

Cathedral of all places. Arieh Ben-Roi starts to investigate, and it’s not long

before he contacts his old friend in Luxor to ask for some assistance from the

Egyptian end. Yusuf Khalifa, meanwhile, has been trying to investigate some

mysterious well-poisonings out in the desert while trying to come to terms with

a family tragedy.

At just over 750 pages, it’s a big book and Sussman didn’t

flinch from dealing with some big issues. Over the course of their investigations

(which are of course connected), Ben-Roi and Khalifa encounter sex-trafficking,

anti-capitalist protests (both of the online and direct-action varieties),

cover-ups and multi-national corporations acting as though they’re above the

law. On a more personal level, the demands of family life and the enduring

power of friendship feature heavily. There are so many threads that at times

you’ll wonder how they’re all going to come together.

And there’s history, of course – the novel is littered

with references to ancient Pharaohs and the Arab-Israeli conflict (although

this isn’t as central a theme as it was in The

Last Secret of the Temple), and the likes of Herodotus and Howard Carter briefly

get drawn into the plot. Then there’s the litany of Arabic and Hebrew slang

that requires a glossary at the back.

As well as this, Sussman treats the reader to portraits

of two great cities – Jerusalem and Luxor – both depictions going beyond what

the tourists see and showing us what life is like for the people who actually

live there, in stark contrast to some thrillers set in interesting locations

that seem to have copied a lot of the descriptive stuff from a guidebook (as he

worked on archaeological digs in the Valley of the Kings, Sussman’s take on the

redevelopment of Luxor in recent years is particularly interesting).

The pace was unrelenting, although as I got to within a

hundred pages of the end I felt the need to slow down as I didn’t want the

story to end. It’s a novel that requires time for the reader to absorb

everything, but it’s also one that you just can’t put down.

If you’re looking for some intelligent holiday reading

this summer, I highly recommend this book.