Being a keen historian, I happen to like visiting cathedrals – although it occurred to me not so long ago that I’ve never been to the one at Canterbury. Visiting said cathedral was therefore at the top of our itinerary when we went to stay with my aunt and uncle in Kent recently.

With its gothic towers, the cathedral truly dominates the

city, and this can be seen as you approach it through the narrow lanes. We were

clearly not alone in wanting to visit it on a warm Saturday, for Canterbury was truly

heaving with tourists from a variety of countries.

After passing through the main gate, we walked around the

outside of this spectacular building before making our way inside, getting to

see some work-in-progress on redoing the lead roof-tiles and the remains of the

old medieval monastery in the process.

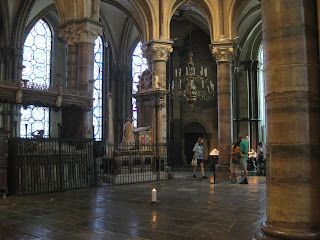

Inside, it’s as magnificent as it looks on the outside. The

perpendicular nave is breathtaking and makes the tourists look tiny. After

marvelling at this, I wandered through the choir to the high altar, took a look

at the Archbishop’s chair (or, to give it its proper title, the Cathedra Augustini) before exploring the side-chapels with their wonderful stained-glass windows. The one dedicated to St Anselm is particularly impressive.

One thing I like about cathedrals is the silence – the air

of peace and quiet that pervades throughout these buildings, in stark contrast

to the bustle and the noise in the streets outside. The noisiest the interior

got was when someone started to play one

of the organs (or maybe play some organ music on the speakers) – nothing loud,

just a quiet background hum that seemed appropriate for the building.

A key point of any tour of Canterbury Cathedral is the spot

at which Thomas Becket was murdered in 1170 by four knights who thought they

were carrying out Henry II’s orders, having apparently overheard that famously

short-tempered King ask who would rid him of that tiresome priest (or words to

that effect). This particular part of the cathedral looks nothing like it did

in Becket’s time – the whole building was extensively rebuilt after a fire

several years after the murder – but the exact spot where he was killed is

still commemorated. The jagged sword effect above it lends a suitably gruesome

air.

In the Middle Ages, Becket’s martyrdom made Canterbury one

of the top pilgrimage destinations in England, which in turn inspired Chaucer to

write the Canterbury Tales (there’s a

distinct parallel between medieval pilgrims and modern-day tourists but that’s

a thesis for another time). His shrine, located behind the high altar in what

is called the Temple

Chapel, was cleared away

during the Reformation – it was said that Henry VIII’s men needed 26 carts to

carry all of its gold and treasures away. Today, the spot is marked by a simple

candle and you can still see the indentations in the floor where generations of

pilgrims knelt before the shrine.

Next to where Becket used to be buried is the tomb of the

Black Prince, who lived in Canterbury

and requested that he be buried in the cathedral. The cathedral’s only other

Royal tomb is opposite, and it’s Henry IV – he who usurped the throne from the

Black Prince’s son. Rather unusually, Henry’s alabaster effigy shows his

fingers missing from his hands. I assumed that this was because some

opportunistic souvenir-hunters had over the years helped themselves, but one of

the catherdral’s excellent guides was on hand to point out that this may in

fact have been deliberate; this is believed to be an early example of an effigy

that shows and accurate portrait, and it is thought that Henry may have lost

his fingers as a result of the serious health problems that plagued him in

later years (no, not the plague – he

had a skin disease that may have been leprosy).

Henry IV, of course, was the King who believed that he would

die in Jerusalem but ended up dying in the Jerusalem chamber in

Westminster Abbey.

Not far from Henry’s tomb is a memorial to the people of Canterbury who died

during the Second World War, when the city was targeted by the ‘Baedeker’

raids. Parts of the cathedral were damaged by bombs, but like St Paul’s the main cathedral itself was not

seriously harmed, thanks mainly to groups of fire-watchers who patrolled the

roof and dealt with incendiary bombs as they fell.

Sometimes it’s the little details that make for a

fascinating experience, and at Canterbury Cathedral there are so many little

details that it probably takes several visits to fully appreciate it. After

reading various memorials, another guide showed us a part of the precinct that

was rebuilt with American money, and to show their gratitude the stonemasons

(even today, several stonemasons are employed by the cathedral, as are dozens

of carpenters) carved a donkey (to represent the Democrats), an elephant (the

Republicans) and an eagle (the US) into one of the pillars. Who knew?

Back in the present, our guide took us to what was the

monks’ Chapter House which is adorned by two wonderful stained-glass windows

that tell the story of Canterbury Cathedral by way of showing scenes from the

lives of several key protagonists in its history, from St Augustine to Becket

to the Black Prince to Simon Sudbury (another Archbish who met a gruesome end)

to Henry VIII to Thomas Cranmer (sensing an ongoing theme with regards to

brutally-killed Archbishops here) and ending with Queen Victoria, who

commissioned the windows.

Now St Augustine

is an interesting character, although he is not to be confused with The Confessions of St Augustine (which

was written by another saint called Augustine). As well as being famous for

bringing Christianity to what would eventually become England, Augustine is the key to explaining why Canterbury, rather than London, is the city with an Archbishop. Back

in the late sixth century AD, Augustine was the man chosen by the Pope to go

and convert the heathen Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Kent was the first part of the British Isles he

landed in, and its king, Ethelbert (or Aethelberht), had his capital at Canterbury. King

Ethelbert duly converted and allowed Augustine to establish a cathedral,

apparently on the site of an old church from Roman times.

Augustine, of course, got to be the first Archbish. Our guide had a slightly

different take on this story, which highlights the role of Ethelbert’s wife,

Queen Bertha. She was already an openly-practising Christian before Augustine

showed up, and is believed to have done much to ensure that he got a favourable

reception.

Outside, we were shown the old water tower and the herb

garden, and were informed that the grass on which we were standing was once the

spot on which the ‘necessarium’, which had a small stream of water running all

the way through it, stood. Nice word. It should be used more often.

By now, we were done with the cathedral for the day, so we

wandered out into the town and looked for somewhere to eat.

No comments:

Post a Comment